LCW’s greatest strength is its power to bring people together and empower them to take ownership of their financial situation, community, and neighborhood.

In the mid-1840s, Yankee entrepreneurs carved out an industrial city in the Merrimack Valley and named it Lawrence after a major financier. They constructed mills spanning entire blocks and drew energy from a dam on the Merrimack River, which runs through the City. Lawrence quickly became home to the enormous Arlington, Wood, Atlantic, Pacific, Pemberton, Washington, and Ayer Mills as well as the thousands of workers who toiled in them. As immigrant labor powered the City, which produced textiles for both the American and European markets, Lawrence became deeply tied to the international economy.

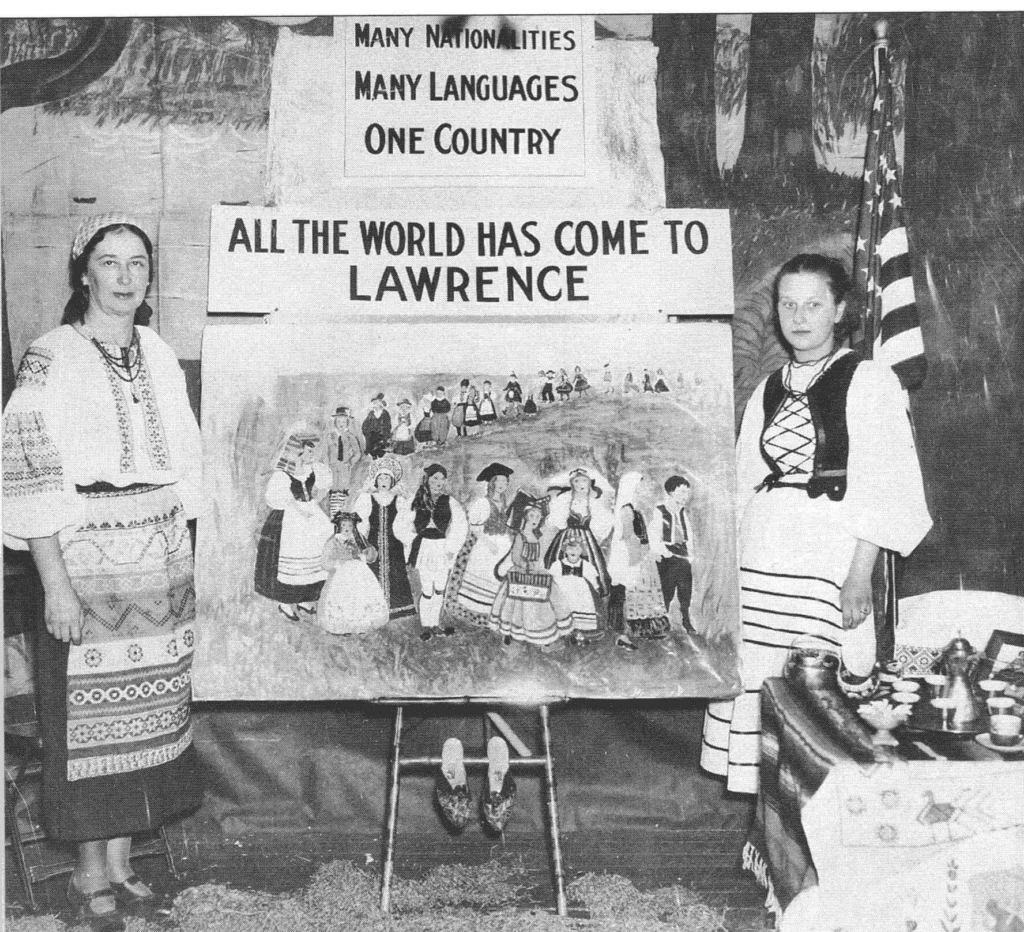

The mill workers arrived in Lawrence in successive waves, drawn by the promise of jobs and with hopes of earning money to send home or start new lives. The first group of workers comprised young women and children from rural New England who began migrating to the city in the mid-1840s. By the end of the century, these workers had largely been replaced by waves of European immigrants, first from Ireland, French Canada, England, and Germany, and then in the early 1900s from Italy, Poland, Lithuania, and Syria. By 1912, the Merrimack Valley had the highest proportion of foreign-born residents in the United States, many of whom lived in Lawrence.

The workers in the Lawrence mills encountered unbearable and exploitative conditions. Women, children and men often worked fourteen hours a day, six days a week, in unhealthy and hazardous factory environments. “I regard my work people, just as I regard my machinery,” said one mill owner. Lawrence workers responded with massive union organizing and in 1912, they staged the first great industrial strike in the United States, known today as the Strike of 1912, or the “Bread and Roses Strike.” Most of Lawrence’s 30,000 textile workers struck for nine weeks during the harsh winter. They came from at least 30 countries and spoke just as many languages, but together, they demanded and won fairer wages and hours and an end to certain discriminatory hiring practices. Today, the Strike of 1912 is heralded as a model for successful inter-ethnic organizing.

Despite the success of the strike, ethnic tensions exacerbated by mill owner policies divided the Lawrence workforce. Although workers called the City home, the property owners, whose primary concern was profit, controlled it. They had built Lawrence to be a machine, not a community; mill profits flowed out of the city and did not benefit residents. In effect, Lawrence workers of the early 20th century saw little improvement in their working conditions or livelihoods.

In the 1920s, textile and shoe producers began moving to the non-union South in search of cheaper labor, ushering in the first stage of industrial decline and job loss in Lawrence. After a forty year period of relative stability, the process intensified again in the late 1960s as more manufacturers moved offshore, also seeking low-wage labor. Between the years of 1969-1988, the City lost nearly half of its remaining 18,000 manufacturing jobs. The recession of the early 1990s generated further unemployment as 5,000 local jobs, or 20% of the City’s employment base, were lost. Almost half of these jobs were in the manufacturing sector.

As some mill owners chose to move their companies offshore in the 1960s, others decided to stay in Lawrence. To ride the economic decline, these owners sought cheap labor and advertised for workers in places like Puerto Rico, initiating another immigration wave for Lawrence that began in the 1970s and continues today. At present, the majority of Lawrence residents are of Puerto Rican and Dominican descent, but there are also emerging Vietnamese and Cambodian populations.

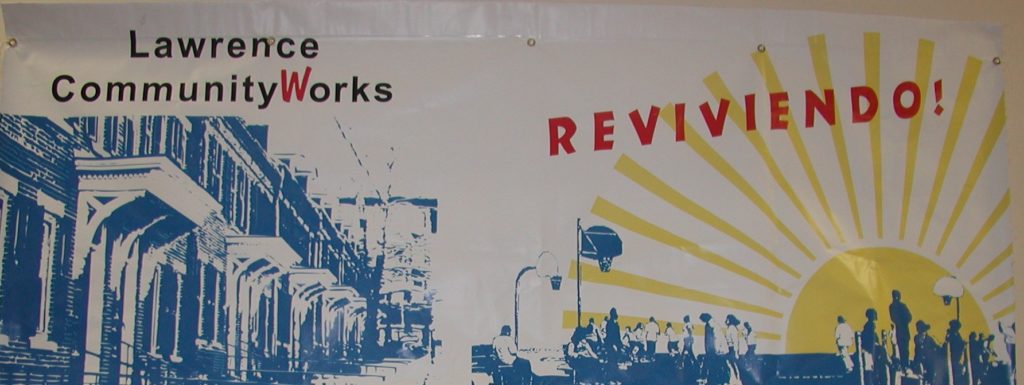

As a city built by and for the textile industry, once-booming Lawrence has never fully recovered from the manufacturing flight that devastated it and other Northeastern industrial cities. Today, Lawrence community members are working together to define a coherent vision for the City’s future, but there are many challenges they face:

Mills: Many of the large mills — once at the heart of America’s industrial economy — now stand underutilized as warehouse space or serving other non job-intensive functions. As buildings, they are costly to rehabilitate for housing and office use and, having no elevators, truck access, or space for parking, they are not feasible for modern-day manufacturing given the demands of modern industry. Many of the City’s properties are also heavily contaminated, a legacy of its industrial past. In the absence of better local work opportunities, many immigrant and Latino residents must work through temp companies to fill in the remaining manufacturing and service jobs that are the underbelly of regional economic prosperity.

Housing: There is a significant shortage of affordable housing in Lawrence. Following the national real estate boom and bust of the 1980s, an arson wave flamed though Lawrence as property investors burned down their buildings to collect insurance. Other properties were abandoned, boarded up, and later demolished, many on the North side of the City. In total, 1,168 housing units in the City were demolished between 1990 and 2001. Moreover, increased rent prices in the Boston area have created greater demand for housing in Lawrence and with this increased demand but limited options, housing costs have risen. Even though Lawrence continues to claim the only substantial source of affordable rental housing in the region, many residents have found themselves unable to keep up with climbing costs. The 2008 real estate boom and subsequent foreclosure crisis, and recent COVID-19 pandemic, are just the latest in a series of macro-economic shifts that continue to buffet the Lawrence market for housing. Today, 40% of Lawrence families spend more than 30% of their income for basic shelter.

Social indicators: The difficult reality that many community members face is apparent in local statistics — today, the community is made up primarily of working class, low- and moderate-income families who face significantly low rates of asset ownership, savings, and investing which leaves them in daily danger of economic catastrophe. Lawrence is still home to a large immigrant population – more than 40% of all Hispanic residents of Essex County live here— and 78% of Lawrence residents speak a language other than English at home. This linguistic isolation hinders many families from interacting with mainstream reputable lenders and creates vulnerability to predatory lending and financial scams. Unemployment and underemployment in Lawrence remain the highest levels in the state: at 15.4% as of February 2021, the Lawrence unemployment is over twice that of the Massachusetts rate of 7.2% (source: Mass.gov/Labor Market Information/Labor Force and Unemployment). Per the U.S. Census Bureau Quick Facts (accessed April 2021), the median household income in Lawrence, MA as of July 2019 was $44,613, which is 55% lower than the state median income of $81,215

While one in three families in Lawrence live in poverty and high city-wide rates of unemployment and low education levels exacerbate the problems, these statistics alone do not tell the full story of present-day Lawrence. Lawrence families are also aspirational and resilient. There is an energy of hustle and perseverance in the city. Those who live above poverty, continue to purchase homes and advance financially. The members and partners of Lawrence CommunityWorks — people who are saving money for their families’ futures, who are building community parks and supporting one another’s efforts, and who are leading the struggle for positive change — tell the story of the City’s rebirth. They have come to Lawrence from different countries and backgrounds, but share the revitalization of Lawrence as a common goal. Together, they have developed a creative vision for the City’s future as a vibrant, productive and healthy community.